Another April, another Autism Awareness Month replete with the same infantilising puzzle piece icons and calls to ‘light it up blue’. Every year, it seems this month dedicated to autistic people has become a hotly contested battleground for autistic people, as we struggle to rise above the cacophony and voice our lived experiences, our joys and the struggles we face in a society that all too often barely acknowledges our presence.

Last year, I wrote a piece for our newsletter on the difference between autism awareness and autistic liberation, arguing that we should focus our efforts on the latter. But as I noted, autistic people, despite becoming increasingly prominent in public life, still struggle to wield any influence over how our neurology is discussed. If we are to talk about how autistic people should liberate themselves, we must first get to grips with how autistic people are side-lined from discussions of our own neurology.

To be autistic is to be pathologized by default. In order to be recognised as autistic, one must first obtain a diagnosis from a qualified professional because, at least as far as medical bodies are concerned, it is still a disorder. The problem here is that there are certain preconceptions our society holds as to what an autistic person looks like. More often than not, they are white, male and somewhere below the age of eighteen (this is certainly the mould I fit when I was diagnosed at age four), and these preconceptions influence not only social perceptions but also the opinions of doctors. It has been widely documented for years that women and BIPOC people are chronically underdiagnosed, which not only means they cannot access vital support systems, but also denies them the vocabulary by which they can articulate their lived experience.

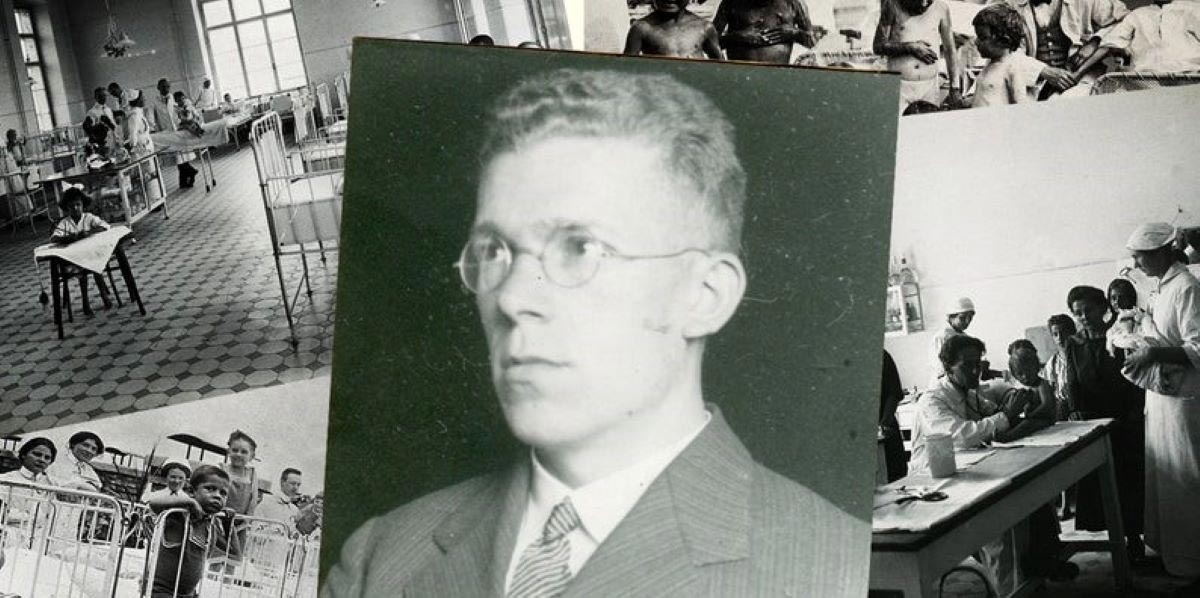

With that said, our demands for recognition must also, by necessity, extend beyond redressing diagnostic imbalances. A cursory examination of autism unfortunately elucidates a history of violence and abuse at the hands of medical professionals and institutions. Hans Asperger, the Austrian psychologist who coined the now defunct term ‘Asperger syndrome’ (now recognised to be just another part of the broader autism spectrum) was involved in the Nazis’ efforts to exterminate disabled people. Just last year, the Judge Rotenberg Educational Centre in Massachusetts, accused by a former UN rapporteur of torturing autistic patients, had its ban on electric shock ‘therapy’ reversed by the Washington D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. These examples are shocking, but more broadly the medicalised approach to autism itself is problematic insofar as it sees autism as a problem to solve, effectively placing the onus on the individual to change in accordance with social norms. A convenient outlook for a society that would rather see us moulded into pliant workers than budge an inch to accommodate our needs.

Of course, obtaining a diagnosis for any neurodivergent condition is no guarantee one’s needs will be met or even acknowledged. Back when I was in Sixth Form, I remember talking to a friend from my old secondary school, who told me that they’d overheard one of the more senior teachers saying they did not believe ADHD to be a real condition, and that those kids at my school who’d been diagnosed were simply poorly behaved. I’ve been thinking about these remarks recently, not just because I’ve started to pursue an ADHD diagnosis of my own, but also because I feel this story is emblematic of how many in positions of authority see neurodivergent people at large. This is why we cannot afford to allow those individuals and systems of power to dictate how our neurology is talked about. If we are to begin addressing the myriad injustices we face on a daily basis, we need to wrest control over our own condition.