Many left internationalists from colonised geographies past and present – the children of empire, transatlantic slavery and oppression – and the comrades allied to us have historically felt the limits or actual violence of politics of the mainstream in the global north. Sometimes, we also feel the limits of left internationalism.

In the UK, it’s often felt like black, Asian and Arab workers are subordinate to the ‘authentic’ white working class. Meanwhile, we know that in historic and contemporary anti-colonial, revolutionary and indigenous struggles in the global south, some comrades in the north – arrogantly or, at best, unconsciously – centre their own perspectives. In the 1950s, the French left told the anti-colonial Algerian resistance to hold off; it was revolution in Paris that would free Algiers. More recently, the Syrian people’s struggle against Bashar al-Assad has been silenced by some as the US (as imperialist) versus Russia (as anti-imperialist) is considered a more important focus.

Left internationalism is, however, a radical act of love. Or at least it should be. An act that recognises and confronts the historical and material conditions that shape our plight – of gross racialised, classed and gendered global inequalities and planetary destruction. An act that demands to see the humanity of everyone and is rooted in a capacity and willingness to learn.

Passing the mic

As a UK-based media publication located in the heartland of capitalist, colonial and imperialist forces, Red Pepper’s challenge to meet our claim of being internationalists is to do more than talk to or about ‘these people’, ‘their causes’ in a tired, radical chic way. This is life and death and all our futures we are talking about, after all. Instead, it demands the creation of spaces for internationalist, indigenous and anti-colonial, anti-racist writers, organisers, artists and editors from these geographies to be heard on their own terms. This is different to the tremendously damaging trappings of ‘identity politics’ that neoliberalism successfully champions. But it does require ‘passing the mic’ and actually learning from comrades outside this island.

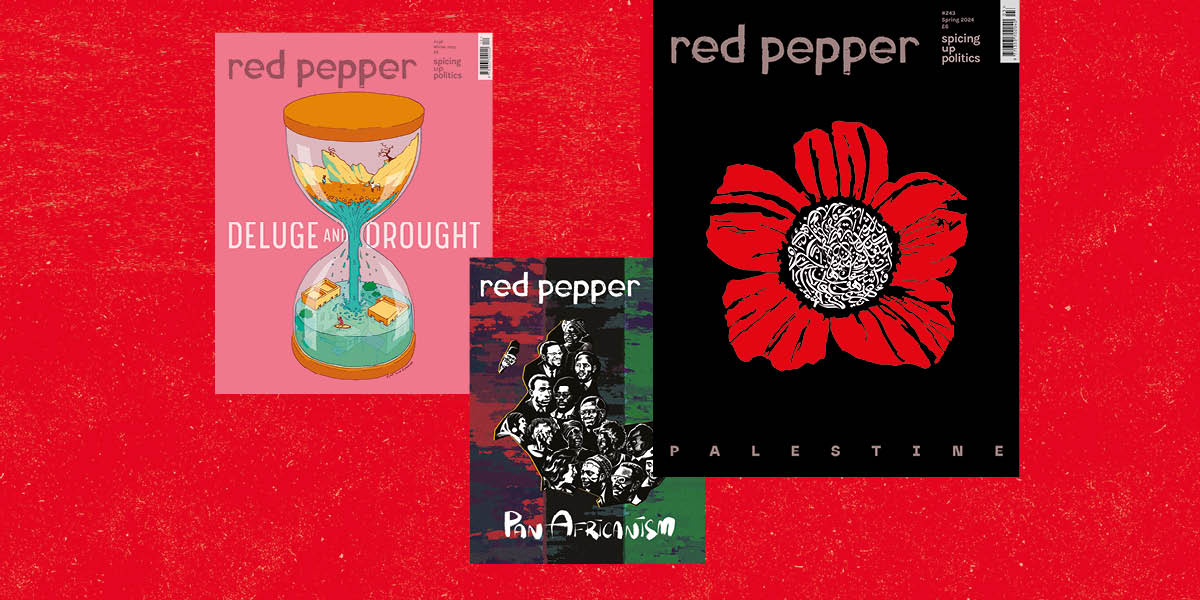

In Issue 238, we covered the floods in Pakistan by giving space to indigenous river movements and connected to comrades working on the ground in relief efforts. In ‘Pan-Africanism’, issue 241, it was organisers, local community and book spaces, artists and social justice centres in Kenya, South Africa, Namibia Libya, Sudan and the diaspora that demanded we appreciate the continued radical potentials of pan-African socialist internationalism for all of us. Meanwhile, our sell-out issue on Palestine was commissioned as the genocide in Gaza was underway. Then and now, our responsibility is to centre voices, images and artists from Gaza, the West Bank, Jerusalem, the Palestinian diaspora and interconnected struggles to remind us that none of us are free until all of us are free.

Red Pepper’s commitment to internationalism is possible because we, as editors, are not just in the UK, but live in, emerge from, travel to and connect to geographies outside it. Sometimes through privilege. Sometimes circumstance. For Red Pepper to continue and improve this radical spirit we must continue to make space for voices and movements from these geographies, as well as allies in and outside, sincerely committed to them, to us.