The Soviet Union, in the 74 years of its existence in one form or another, was a society that was all about building. The Soviets claimed in the 1970s to have ‘built’ socialism, and while they never claimed to achieve communism, the communists were constantly ‘constructing’ its ‘foundations’. Engineers were exalted, immense dams were built, housing estates the size of entire English cities were erected from concrete panels by cranes, on rails; even writers were considered ‘engineers of the soul’.

By 1991, most of the built environment in the former Russian empire consisted of structures constructed after 1917, and particularly, between the death of Stalin in 1953 and the fall of the Berlin wall at the end of the 1980s, Soviet architecture underwent several distinct periods. There was utopian speculation in the late 1910s, dynamic constructivism in the 1920s and early ’30s, neoclassical Stalinist wedding cake baroque until the despot’s death, a concrete panel functionalism under Khrushchev and Brezhnev, and, finally, a cultish dystopian ‘paper architecture’ mocking the entire project under Gorbachev. But what happened after? Did the 15 constituent republics that emerged from the collapse at the end of 1991 manage to construct something substantially better, worse, or just different, after this immense failed attempt to construct socialism fell apart?

Scorn and privatisation

Early on, the entire built legacy of the USSR was subjected to immense and undifferentiated scorn. A few leaders promised to demolish as much as they could of the huge public housing projects and monumental state complexes that dominated urban space and made very clear you were not in America. But the drastic economic contraction of the 1990s – which remains the deepest economic depression in the historical record anywhere – meant that this was never plausible.

What happened instead to the public housing stock in nearly every republic was instant privatisation, with residents becoming the owners of their flats – hence creating an immediate property-owning class, though the communal areas, and crucially, the land, of the estates remained state-owned. This was an indicative example of how much post-Soviet capitalism would cannibalise the Soviet legacy. Indeed, some of the major building projects post-1991 are fundamentally Soviet, with examples ranging from Moscow’s grandiose neo-Stalinist Museum of the Great Patriotic War (commenced in 1986, opened in 1995) or the deep, decorative, atmospheric stations of the Almaty Metro in Kazakhstan (begun in 1988 but not completed until 2011).

In terms of new buildings, the first place to construct on a large scale was Moscow, which was flooded with dubious money, as the ‘oligarchs’ emerged out of an alliance between younger party bureaucrats, industrial managers and organised crime. The oligarchs and their henchmen favoured a jokey, kitsch sort of postmodernism, which often alluded to the domineering aesthetics of high Stalinism – a quintessential example was the Triumph Palace, a luxury housing tower designed in imitation of the ‘seven sisters’, the baroque skyscrapers built in a ring around Moscow during the early 1950s, in Stalin’s last years. This went alongside tsarist kitsch that aimed to redress Stalin’s demolitions, like the reconstruction of the grotesque 19th-century Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. A few cities, meanwhile, built similarly crazed, decorative architecture to redress historical grievances – the city of Kazan, in the Republic of Tatarstan, built a hulking new baroque mosque within its medieval kremlin.

Some distance from all this is the neat, polite, Euro architecture that was built in the westernmost republics of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, which were annexed to the USSR in the 1940s. Estonia, in particular, has been an interesting place for good, thoughtful, often small-scale modern architecture, as indeed it was within the USSR. The standout is Narva town hall, in a border city destroyed by war and Soviet planners: a structure that deliberately presents a ghostly echo of a 17th-century building that once stood on its site, rather than simply reconstructing it – an engagement with the past that stressed the holes and absences of memory and history, rather than using it to settle scores. Despite their sometimes caricatural official anti-communism, cities in the Baltic countries have also been among the few to properly renovate and look after their Soviet-era mass housing, whereas a city like Moscow threw gleaming new buildings up against working-class blocks of flats that were literally left to rot.

‘Oligarchitecture’

In massive contrast to the generally polite turn of architecture on the Baltic was central Asia. Despite a brutal colonial history, many here were reluctant to leave a modernising USSR in which they were increasingly left alone by Moscow. In 1991, huge majorities in each Asian republic voted in favour of retaining the union. After that, democratic Kyrgyzstan and dictatorial Tajikistan were thrown back into the third world by war and deindustrialisation, but Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan became petrostate dictatorships run by their 1980s Communist Party leaders. Turkmenistan became one of the world’s most insular and inaccessible countries under Suparmurat Niyazanov – who renamed himself ‘Turkmenbashy’ and commissioned gold statues of his person, while oil revenues were spent on turning Ashgabat into a kitsch neoclassical capital of gleaming marble, gold and empty space.

More international, let’s say, was Kazakhstan, whose dictator Nursultan Nazarbayev was advised by Tony Blair. In the 2000s and 2010s, a new capital, Astana, carved out of the old Russian-dominated Soviet industrial town of Tselinograd, was largely designed by the British architect Norman Foster, with ‘iconic’ buildings such as the pyramidal Palace of Peace and Reconciliation.

By the 2020s, with a certain bitter irony, the grandest of Moscow’s grand projects under Putin’s increasingly nationalist and violent regime were based on a reimagining of the architecture of the early communist vanguard

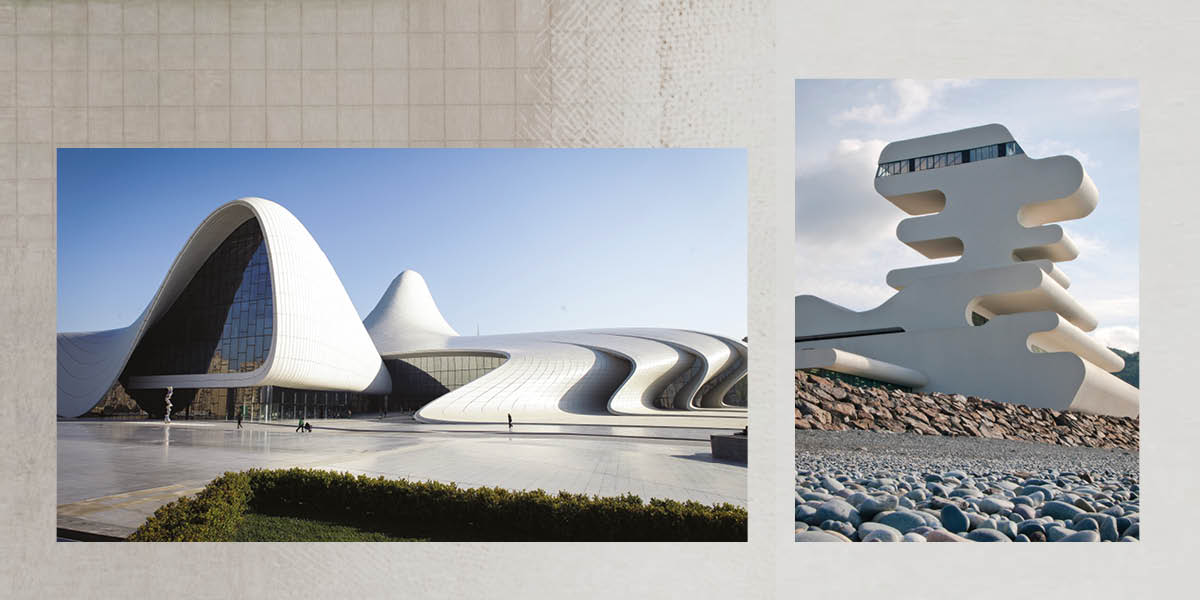

Foster’s buildings in Astana sum up a certain moment of ‘oligarchitecture’ in the 2000s – swooping, dramatically engineered, somewhat useless structures for the arts that were dropped around petrostates in the Gulf and within the former USSR. Baku, in Azerbaijan, built the most spectacular of these, the Heydar Aliyev Centre, by the British-Iraqi designer Zaha Hadid. The man this flowing, billowing, very 21st-century structure was named after was a long-running KGB officer, a former leader of the local Communist Party, a post-1991 dictator and father of the current dictator Ilham Aliyev.

Nearby Georgia, though more democratic and much messier, also went in for famous western architects. Its leader after the 2003 ‘rose revolution’, Mikheil Saakashvili, would read western architecture magazines and online sites like Dezeen or ArchDaily, and then hire designers on the basis of the pictures he’d seen. Some of the resultant buildings were terrible, like the Tbilisi buildings of the Italian Massimiliano Fuksas; some were rather fine, like the new checkpoints on the Turkish border by the German architect Jürgen Hermann Mayer, but all were forced through without much consultation or interest in the existing context of complex cities like Tbilisi or Kutaisi. A fellow enthusiast for this sort of over-engineered, photogenic architecture was Saakashvili’s great antagonist, the ‘pro-Russian’ billionaire and current de facto ruler Bidzina Ivanishvili, who commissioned the Japanese postmodernist Shin Takamatsu to design him a gleaming high-tech personal castle overlooking Tbilisi.

Architecture from below

On this evidence, the ‘freedoms’ of capitalist transition mostly meant the freedom for an emboldened elite to impose themselves more grossly on everyone else. Likely as a consequence, the 2010s saw increasing interest in Soviet architecture across the region. There were campaigns to save from demolition, or raise awareness of, the planned interwar city of Yerevan, Armenia; the post-war reconstruction of Minsk as a neoclassical showpiece; the 1970s orientalist futurism of Almaty or Tashkent; the constructivist utopian projects of 1920s Moscow or Kharkiv; the Bauhaus buildings of Zaporizhia; or the postmodernist post-Chernobyl new town of Slavutych, built in Ukraine in the USSR’s last years. Ironically, these often mobilised a liberal civil society, which, in the 1990s, was axiomatically ultra-hostile to the Soviet legacy.

In a few cases in the 2010s, there was even an evanescent grassroots architecture from below, particularly in Ukraine between the Maidan revolution of 2013/14 and the full-scale Russian invasion of 2022. Artistic groups like Kyiv’s Visual Culture Research Center or the initially Donetsk-based Izolyatsia built temporary, lightweight structures that were intent on encouraging dialogue and enjoyment in genuinely public space. In 2018, a Polish and Ukrainian team managed to crowdfund a new theatre in a park in the city of Dnipro, open to anybody who wanted to use it.

These more democratic, liberatory projects remained exceptions. By the 2020s, with a certain bitter irony, the grandest of Moscow’s grand projects under Putin’s increasingly nationalist and violent regime were based on a reimagining of the architecture of the early communist vanguard. Century-old revolutionary structures that had rotted for decades, like the incredible Rusakov Workers Club by Konstantin Melnikov or the Narkomfin Communal House by Moisei Ginzburg, were carefully and lovingly restored. A 1907 power station opposite the Kremlin was transformed into a glassy, retro-futurist new modern art museum for the VAC art foundation. A dramatic avant-garde bakery, one of several automated bread factories built across the Russian capital at the end of the 1920s to help liberate women from ‘kitchen slavery’, was renovated and reopened as the Zotov Constructivism Centre. In the same year, Russia launched its tanks over the border towards Kyiv, Dnipro and Kharkiv, and the architects behind these structures – internationalists and socialists, most of them – turned, not for the first time, in their graves.