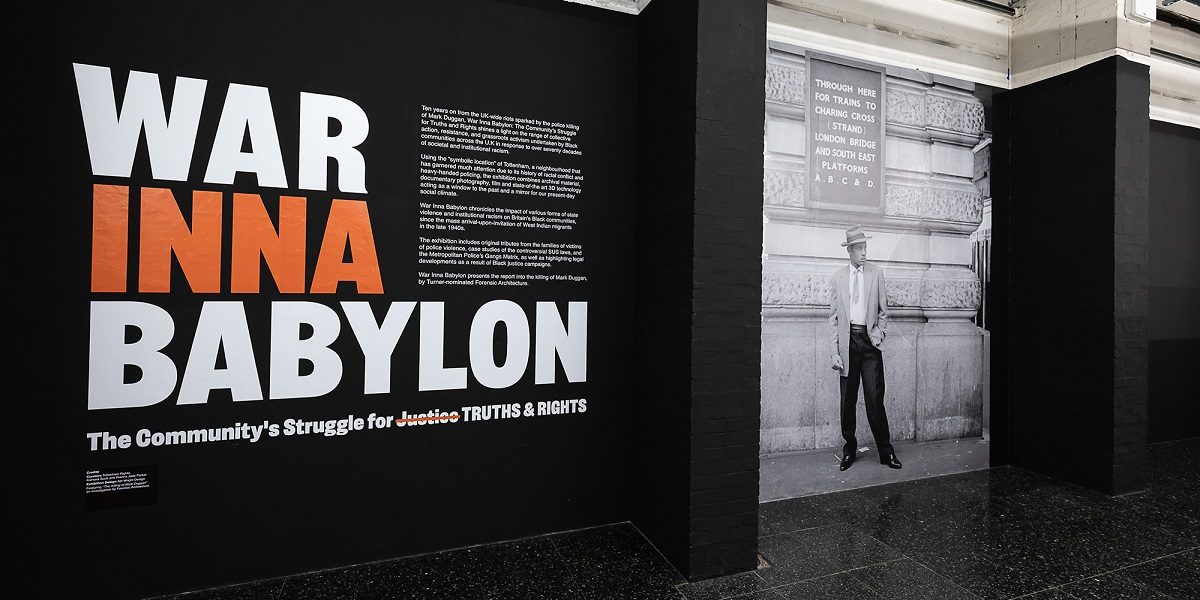

Exhibition: War Inna Babylon: The Community’s Struggle for Truth and Rights

Location: The Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

Curator: Tottenham Rights, Kamara Scott and Rianna Jade Parker

Date: 7 July – 26 September 2021

Moments make history – a split second captured and contained within the frame of context – and all it takes is a moment for history to be made. One moment, two shots: all it took for an afternoon in August 2011 to turn and for Mark Duggan to have his life taken by the bullet of an armed officer. A local community, the picture of grief and disbelief, led a peaceful demonstration to Tottenham Police Station in search of answers. Later, a separate contingent – from near and from afar – let their pain and disaffection play out in the streets with momentous, deleterious force.

A close crop in the mainstream showed these mostly Black, working-class bodies assuming insurgent postures – much of their humanity denied, mile-long threads of history conveniently dismissed. Now a decade floods the aperture between the inciting act, the subsequent outcry and riotous unrest, and the present moment. And with there being no better time than the present to reappraise the past, there is no more timely exhibition than War Inna Babylon: The Community’s Struggle for Truth and Rights – as curated by Tottenham Rights, Kamara Scott and Rianna Jade Parker – currently showing at the ICA until 26 September.

It was Stafford Scott – father of Kamara and leading figure within community interest group Tottenham Rights – who received a call heralding Duggan’s shooting before Duggan’s own parents or partner were made aware. In fact, both the Metropolitan Police opted not to contact Duggan’s kin at all. It would be through evening news reports, partial and patchy, that vital information would filter down to those who deserved to know first.

In the absence of the frame of historical context, a number dismissed the Met’s lack of direct communication as a casual oversight. In the absence of conclusive footage capturing the scene of the shooting – but in spite of contradictory officer testimonies, concerns about ‘procedural failings’ and accusations of institutional collusion – a 2014 inquest found Duggan’s death to be a ‘lawful killing’. And it is in the absence of justice, a term pointedly redacted from the exhibition’s subtitle, that War Inna Babylon derives its form and trains its focus.

Assemblages of history

The exhibition is split over two floors, including interstices and spatial voids such as the stairway between the Lower and Upper Gallery (where you find Garnet Dore’s Broken Lives, a stirring assemblage of paintings in fractured frames) and the lightwell that emerges overhead after half a flight (where you find Remee Bailey’s Message Pending, a canopy of forthright protest banners). Taken together, a social history of a place, of a people and of a struggle is illuminated, enriched and, finally, legitimised.

In excising the pursuit of justice from the formal agenda, War Inna Babylon appeals instead to the exercise of ‘witness work’ – which, to lean on the scholarly insight of Ladi’Sasha Jones, is best conceived as the Black feminist ‘engineer[ing] [of] poetic tools of resistance and provocative encounters’. And found within this exhibition’s toolkit is a mixture of archival footage, documentary photography, filmic compositions, 3D technology and ephemera – with artwork by Dore and Kimathi Donkor rounding out the pack with considered flair.

Remee Bailey’s ‘Message Pending’

CREDIT: TIM P. WHITBY/GETTY IMAGES FOR ICA

Maximalist elements such as Parker’s Us an’ Dem, a nine-screen installation broadcasting an eye-catching and contrastive edit of vox populi and scenes of a resistive nature from the 1980s, are nested within and offset by Abi Wright’s taut exhibition design. Black, white and blood-orange are Wright’s chosen hues for walls, cabinets and in-situ text – a palette that communicates the spark of a freshly struck match – with a smattering of arches the structural choice to create the portals needed to order, access and appraise the all that has come before.

Boundaries are located and bridges formed between moments in time: chapters of history and correlative movements are brought into alignment through thematic sequences that track the postwar arrival-on-invitation of West Indian immigrants (Routes) to the late-century production of a singular Black British identity (Raggamuffin). Tributaries of culture and resistance meet and pool at these, and many other, critical junctures. Meanwhile, the police – their modes, their methods – are a leviathan that never fully recedes from War Inna Babylon’s line of sight.

It is made patent how and why Black trust in statutory governance has sunk, generation after generation

This land is no El Dorado, its law enforcement no celestial order: from the ‘colour bar’ restrictions on employment to the institutional ritual of ‘n***** hunting’ – both commonplace prior to the founding of the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination in 1965 and the controversial passing of the amended Race Relations Act in 1968 – state-sanctioned hostilities and brutalities are shown to have long hallmarked this environment.

These are dark depths. It is made patent how and why Black trust in statutory governance has sunk, generation after generation. But matters do crest. War Inna Babylon compels the bonds of and between the Black community to surface, and makes a point to laud the host of working-class Black women who have contended with staggering waves of violence – generation after generation – to lead with care and ‘lift as they climb’.

The personal is political

Scott leads a walk-through a couple of times a week and, though not a prerequisite, it is highly recommended that you take the time and tag along if possible. A savvy orator and peerless storyteller, Scott’s tour serves not only to expound on but infuse the main – steeping the displays in a potent brew of the playfully digressive and purposefully reconstructive. At intervals, Scott impresses upon those in attendance that the events of ten years ago did not happen in isolation.

He would know: growing up on Tottenham’s Broadwater Farm Estate in the 1970s – audacious but erudite, ragga through and through – Scott was subject to the heavy-hand of the constabulary and arbitrary humiliations of ‘sus’ laws. He lived through 1975, 1976, 1980, 1981, 1985 and 1987 – all years marked by resistive uprisings within Black communities across the country, from Leeds to London. He witnessed, time and time again, the truths obscured and rights suppressed by the Met and the judiciary.

You are told, then, but you are also shown: a discrete arc of Scott’s life – as it has interrelated with the project of the police and the project of community – can be plotted through the Lower Gallery displays. On the wall, ‘1st Class Citizenship’ – an accomplished pencil sketch produced in 1979 by Scott during a stint in prison. And in a cabinet, Scott’s certificate in Community and Youth Work from the now-defunct Bulmershe College of Higher Education, alongside a letter of apology written to Scott by a Met Deputy Assistant Commissioner, dated 1988 and 2018 respectively.

The years stack up. Personal, political and collective histories collide – and War Inna Babylon allows them to do so. It is unwieldy. It is also thoroughly effective: you begin to comprehend how immense – and how unending – the work of bearing witness, of resistance, is. There are no close crops here.

A wide-angle view is maintained through the displays in the Upper Gallery, also – with loss, as a lived and thematic reality, foregrounded. The darkened plinths of Five Families of Tottenham, a sequential video tribute from the loved ones of locals who have died in police custody, honour the dimension of lives lived in addition to analysing the circumstances of fateful ends. It is stark in its design, deliberately humane in its execution, and all the more haunting for both.

Absences are keenly felt and thoughtfully unpacked: the brother of Roger Sylvester, who was unlawfully killed by police in 1999, recalls a highly empathetic Arsenal fan with an ‘excellent memory’ and a tendency to ‘caress’ his dinner plate as he ate; he goes on to describe Roger’s death, along with the deaths of other Black people in custody – a total body count of 124 since 1990 according to the charity INQUEST – as an ‘initiation’ for the family members left behind.

The opening to the exhibition

CREDIT: TIM P. WHITBY/GETTY IMAGES FOR ICA

Such clear-sighted remarks and tender reflections dare you to try and leave them behind as you move on to the white-walled room containing Tottenham Rights’ anatomisation of the Met’s Gangs Matrix and Forensic Architecture’s The Killing of Mark Duggan – the exhibition’s double-pronged coda.

The former prong is a reminder of the ways in which Black, working-class bodies are pathologised, surveilled and, subsequently, targeted – the institutional database, it can be reasoned, a digital analogue of the institutional hunts of the 1960s. While the latter functions as a commanding evaluation of the events leading up to Duggan’s death – driven by scientific precision and a clear sense of purpose – as well as a fierce pushback against many of the narrative interpretations, mainstream images and judicial assessments spun since.

Recordings, computer-aided reconstructions and sheer reams of written analysis situate the ‘split second’ – the ‘most lethal of temporal exception’ in the words of Forensic Architecture’s founder, Eyal Weizman – within the frame of racialised, obfuscatory thinking, where it belongs. And outside this frame? All other moments that have made up Black life in Britain: the battles fought, the lessons learned, the initiations, the exclusions, the losses and the gains.

War Inna Babylon holds you in an embrace with these moments, commands you to perceive their manifold frequencies, and releases you renewed and ready. Ready, as John Berger put it, to ‘wait in solidarity’; ready to use ‘what we have inherited from the past and what we witness’ to build our courage; ready to ‘resist and continue resisting in as yet unimaginable circumstances’ – in a world that remains, as yet, uncaptured and uncontained.