Should citizens be compelled to vote? Most of the world’s democracies say no, but a few compel electors to turn up at the ballot box, even if leaving them free to deface their ballot or leave it blank. A travesty of democracy? Or a necessary condition for it? The case against is that it is an undemocratic infringement of a person’s liberty; the case for is that it enhances government by the people.

How it works

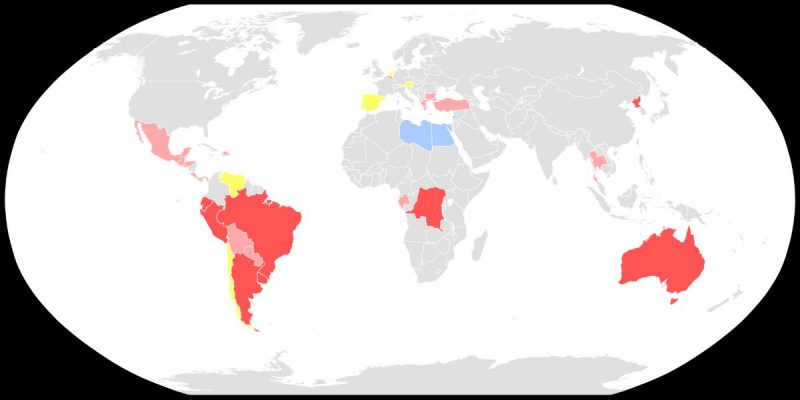

Voting is compulsory in only 19 of the world’s 166 electoral democracies, and strictly enforced in nine of these, including Australia, where I live. Mandatory voting was first mooted here in the middle of the 19th century and debated intermittently until its adoption in 1924.

Objections to it were overwhelmingly practical: that it would be too difficult to administer. But by far the most common argument in its support was that governments would be elected by the majority of eligible voters, not just the majority of those who voted, and would thus have greater democratic legitimacy. Some advocates of mandatory voting in other parts of the world, especially in Latin America, hoped that compulsory voting would dilute the effects of the mobilisation of working-class voters by compelling the rich and comfortable to vote. Whichever, the intention was the same: to bring out the whole nation on election day.

Turnouts in countries with compulsory voting are substantially higher than in those without. In Australia it is always above 90 per cent of registered voters. The turnouts in Latin American countries that enforce compulsory voting, though not as high as in Australia, are well above the low points of turnouts in Britain and the United States.

In the 2016 US presidential election the turnout was in the high fifties. Donald Trump did not have the support of the majority of voters, but neither would Hillary Clinton had she won. Britain’s 2016 decision to leave the EU was carried by a slim majority of the 72.2 per cent of registered voters who turned out.

Compulsory voting in Australia – Not just for the comfortable

Majoritarian arguments for compulsory voting in Australia are a close companion of egalitarianism. If government is to deliver the greatest happiness to the greatest number, then the greatest number need to vote. We know from voluntary voting systems that the poor and marginalised are least likely to vote – and so do those running for office.

With compulsory voting, however, no political party can afford to ignore a substantial group of voters. Policies pitched only at the comfortable just won’t fly. Without compulsory voting, the Australian Liberal Party would have abolished our national health system, Medicare, long ago, relying on the fact that those who needed it most were least likely to vote.

Laws and practices regarding voter registration vary widely across democracies. In Australia, registration has been compulsory since 1911 and is made as easy as possible – in contrast to southern US states where voter suppression begins with onerous registration requirements. Similarly, if voting is compulsory, then it has to be made easy for citizens to comply. In Australia, the Australian Electoral Commission manages elections in a massive coordinated logistical exercise, which sees polling booths in Australian Antarctica and the central desert, as well as easy postal and early voting.

Engagement and integration

Without compulsory voting, parties have to work hard to get out the vote, tempting them to focus on divisive issues. Moral outrage is a great motivator, especially if backed by religious conviction, but this kind of politics can erode social cohesion. Compulsory voting and registration, however, can foster more stable political engagement.

Because young people reaching voting age are compelled to vote, they must pay at least minimal attention to parties, leaders and issues. Over the many years I taught first-year Australian politics, by far the most common reason for doing the subject was that the student was about to cast their first vote. After a few elections, they will be better informed and more interested than had voting been left as a matter of choice. Some partisan feelings are likely to have developed and voting to have become a habit.

This argument also applies to the integration of new immigrants. Acquiring Australian citizenship, they at once acquire the obligation to vote, which contributes to their integration into Australian society. Unfortunately, the right to vote does not yet extend to permanent residents, even if they have lived here and paid taxes for years. In New Zealand, by contrast, permanent residents can vote after a year of continuous residence.

In three years, Australia will celebrate a centenary of compulsory voting. Since the earliest opinion polls in the 1940s, support for it has never been less than 60 per cent, and in recent decades has bounced around the 70 per cent range. Most encouragingly, a greater majority, around 80 percent, say they would vote even were it not compulsory.

Judith Brett is an emeritus professor of politics at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, and the author of From Secret Ballot to Democracy Sausage: How Australia got Compulsory Voting (Text 2019)

Compulsory Voting Fact File

- The concept of mandatory voting can be traced back to Athenian democracy, which held that it was every citizen’s duty to participate in decision-making. While attendance at the assembly was ultimately voluntary, people not participating could be met with scorn.

- Belgium has the oldest still existing compulsory voting system. It was introduced in 1893 for men – but only in 1948 for women, following universal female suffrage. In 2018, voter turnout was 90 per cent.

- Equating in kind to similar civil responsibilities such as taxation, jury duty, compulsory education or military service, voting in democracies is regarded as one of the ‘duties to community’ mentioned in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

- In 2015, Barack Obama said: ‘It would be transformative if everybody voted – that would counteract money more than anything… The people who tend not to vote are young, they’re lower income, they’re skewed more heavily toward immigrant groups and minorities… There’s a reason why some folks try to keep them away from the polls.’

- A 2015 study of compulsory voting in Switzerland found that the enforced rule significantly increased electoral support for leftist policies in referendums by up to 20 percentage points. A 2016 study found that compulsory voting reduces the gender gap in electoral engagement in several ways.

- According to the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA), only 27 nation states use compulsory voting laws – and only 15 actually enforce them. A further 13 countries have introduced mandatory voting, only to later abolish the practice.

- Turnout in countries with compulsory voting is on average only 7 per cent higher than in countries without it. High turnout can be achieved without penalising non-voters – as Sweden (87 per cent in 2018), Denmark (85 per cent in 2019), and South Korea (77 per cent in the 2017 presidential election) all prove.

- Of the 23 states ranked as ‘full democracies’ in The Economist’s Democracy Index 2020 only four have mandatory voting laws (Australia, Luxembourg, Uruguay and Costa Rica – and the latter does not enforce it) – as do three ‘authoritarian regimes’ (Egypt, Gabon, and the DCR).

- In 2002, Eduardo Galeano wrote: ‘In Argentina, as in many other countries, the people vote, but do not choose. They vote for one person, and another governs: the clone governs. The clone… does the opposite of what the candidate promised during the campaign… A recent poll showed that only six of ten Argentines… believe in democracy.’

- Legal loopholes that allow non-voters to escape punishment can be counter-productive: where only registered voters are required to vote, registering itself can be disincentivised.

Uruguay: Beyond compulsory voting

According to the Economist’s annual ‘Democracy Index’, Uruguay is one of very few ‘full democracies’, ranked above the UK, France and the US. It would have been higher, but the evaluators criticised compulsory voting as contrary to liberal principles. Its mechanisms for disciplining non-compliance with compulsory voting are the world’s most severe.

Until 1971, when most of the left united in the Frente Amplio (‘Broad Front’, but in effect a party, with a common programme and joint candidates for national and local elections), government rotated between the right-wing National and Colorado parties. A full transformation came in 2004, when the Frente Amplio won a parliamentary majority and then governed for three terms, until March 2020.

The Uruguayan left’s commitment to compulsory voting first came to the fore with the national constituent convention of 1916-17, when it was backed by left constituents. Emilio Frugoni – the founder of the Socialist Party, the ‘mother’ party of much of the contemporary left – argued that compulsory voting enabled the development of an ‘active citizenship’ and a ‘superior political order based on self-government’. The convention rejected compulsory voting but agreed to the mandatory registration of the population in the civic register, the principle of proportional representation and secret ballots.

Long-term perspective

Compulsory suffrage was eventually incorporated in 1934, in the aftermath of a military putsch. Its definitive legislative regulation and application was approved in 1971 by a parliament that faced intense social, economic and political conflict, including the guerrilla Tupamaros, massive strikes and the electoral rise of the far right. It could not prevent the collapse of Uruguay’s democracy in June 1973, however. As elsewhere in South America, the country suffered a decade of brutal military dictatorship.

Initially, compulsory voting benefited the right, but with demographic change and the disappearance of the older, more conservative electorate, this bias ceased. At present, it has little impact on electoral results. In 2019, the Frente Amplio lost the presidential election and the right returned to government, although the left remained the largest bloc in parliament. The Frente Amplio will most likely win the elections scheduled for 2024.

Compulsory voting in Uruguay should be understood from a longterm perspective. Unlike many other countries, Uruguayan politics is strongly election-driven with very low abstention rates. For more than a century, electoral participation has never fallen below 75 per cent.

In the period 1942-2014, average voter turnout rose to 84 per cent and since compulsory voting to around 90 per cent. Recent surveys indicate that most Uruguayan citizens are ‘interested’ or ‘very interested’ in politics – a rate much higher than other Latin American nations.

High numbers of citizens would vote voluntarily. Regular national surveys show that support for compulsory voting increases among people over 45 and with strong political allegiances. No political party in Uruguay, on the left or right, openly questions compulsory voting.

The highly-respected political scientist and former Frente Amplio senator Constanza Moreira argues that under voluntary voting there is ‘less involvement of subordinated social sectors, which in turn makes the government less interested to develop policies for these sectors. In other words, voluntary voting is elitist and generates elitist results, which is why I support compulsory voting.’

Progressive referenda

Beyond electoral politics, trade unions, housing co-operatives, student associations and feminist and environmental organisations often join forces to promote progressive constitutional reforms or oppose regressive legislation through direct and participatory democracy. In the past three decades, Uruguay has had 15 people-initiated referenda. In 1992, it became the first country in the world to block the privatisation of public enterprises by popular vote, and in 2004 to amend the constitution to declare water a human right and impossible to privatise.

In the past year, in the midst of the pandemic, the Frente Amplio, labour and other movements collected 795,000 signatures (the equivalent of more than 15 million in Britain) calling a referendum to repeal the ‘Law of Urgent Consideration’ (LUC) – a neoliberal austerity and anti-labour law. The electoral court is now certifying the signatures (and fingerprints) before calling on all Uruguayan citizens to vote to accept or reject the LUC.

This article first appeared in Issue #233, ‘Democracy on the Wing’. Subscribe today to read more articles and support fearless independent media