Amidst the protean revolutionary tumult of 19th century Europe, left-wing political thinkers set their minds to a form of political action that would better achieve a unity between words and action. Plenty of ink had been spilled attempting to analyse and understand the world, but as ever, the question persisted of how to change it.

One idea would find particular purchase during the late-19th and early-20th century, and also go on to profoundly influence popular understandings of the connection between politics and violence: propaganda of the deed.

Forged sometime during the 1870s through the theoretical cooperation of Russian revolutionaries like Mikhail Bakunin and Italian anarchists who would help to crystallise the theory, it sought a departure from printed and oral propaganda detached from people’s immediate political contexts in favour of ‘concrete insurrectionary activity’.

Though its definition is both broad and contested, propaganda of the deed describes radical, violent political action carried out in public and against the infrastructure, assets and even members of the ruling class with an objective of actualising insurrectionary thought in the public consciousness and fomenting wider political revolution.

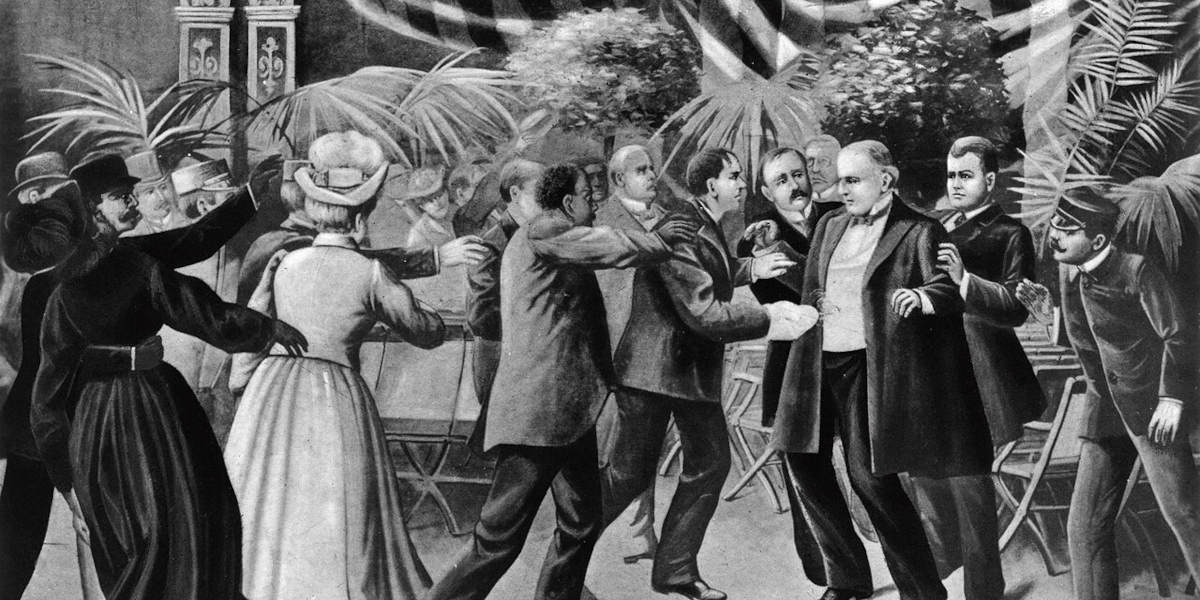

By the 1880s, the deed elevated from theory to action, with numerous attempted assassinations of Heads of State in Germany, Spain, Italy, and particularly Tsar Alexander II in Russia in 1881. By the 1890s, it had inaugurated what Richard Bach Jensen calls a ‘decade of regicide’ with political leaders from Prime Ministers to Empresses falling victim to anarchist assassinations.

Explosive acts

In terms of its propagation, however, the deed owes much to another 19th-century invention: Dynamite. With its wide industrial uses and comparative availability, Dynamite placed explosive power, previously the reserve of professional state militaries, in the hands of non-state actors.

In its historical period, the deed arguably reached both its denouement and zenith in September of 1920 when Mario Buda, an Italian anarchist who subscribed to a strain of anarchism promoted by Luigi Galleani, detonated a horse carriage laden with dynamite across from the offices of J. P. Morgan in downtown Manhattan.

Though he missed his target, J. P. Morgan Jr., Buda killed 38 and injured over 140, mostly working class clerks and accountants. What he had succeeded in, however, was creating a primitive form of what would later become the ‘car bomb’.

For all its spectacular potential, the deed’s strategic weakness lay in the same place from which it emerged. In their desire to move beyond theory to praxis, the radicals had settled on a strategy of violence and terror in which it was difficult to locate any theory. The bloodshed it promoted alienated the populace while advancing a politics of nihilism.

The deed is now most legible in that wide-ranging repertoire of non-state violence called ‘terrorism’. Given its nihilist bent and questionable theoretical ballast, it is unsurprising that the deed has had greater propagandistic utility in the hands of right-wing white nationalist groups.

Beginning with white nationalist group The Order in the 1980s, a chain of memetic violence can be traced which extends through countless socially alienated killers like Timothy McVeigh, Anders Breivik and Brenton Tarrant for whom mindless violence is both theory’s point of departure and destination.

Strategists of revolutionary political violence would do well to remember the old adage about the gait and timbre of a duck – and that political acts that look like nihilism are unlikely to advance an agenda of worthier substance.

Further reading:

- Zoe Baker, Means and Ends: The Revolutionary Practice of Anarchism in Europe and the United States (2023, AK Press)

- Caroline Cahm, Kropotkin and the Rise of Revolutionary Anarchism 1872-1886 (1989, Cambride University Press)

- Jean Grave, ‘Means and Ends’ (1893) in Robert Graham, Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, Volume One: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300CE – 1939) (2004, Black Rose Books)

- Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism (2009, PM Press)