This time, everyone saw what happened.

It was a Tuesday morning in June, and a yellow car was driving through the streets of Nanterre, Paris. Three teenagers were on board a rental car that drove into a bus lane. Two policemen turned on their revolving lights and asked the driver to pull over. His name was Nahel Merzouk, and he was 17-years-old.

Nahel kept going and drove through a red light. The two policemen caught up to him. Feet on the ground, weapons drawn, they instructed him to roll down the window, which he did. One of them shouted, ‘I’ll drive a bullet through your head’ then fired at him. After a shot in the chest, Nahel died.

Nahel’s story follows so many other deaths at the hands of the police in France. The common thread between the targets is that they have all been mostly non-white, working-class men. What has been exceptional about Nahel’s case, is that this time the whole country witnessed the execution.

Everyone saw the policeman open fire on a teenager who posed no physical threat. Instead of being sentenced to a year’s imprisonment and a €7,500 fine — the maximum penalty for this type of offence — he was shot point-blank. The shooter was a soldier who had previously served in Afghanistan and was a former member of the ‘motorised brigades for the repression of violent action’ (BRAV-M) which has historically faced much criticism.

The morning of the tragedy, Nahel’s mother had told him to be careful. Soon she would say, ‘He was my life, he was my best friend, he was my son, he was everything to me.’ Nahel played rugby. School wasn’t his thing; he delivered pizzas. He was a regular kid from the banlieue, according to those who knew him.

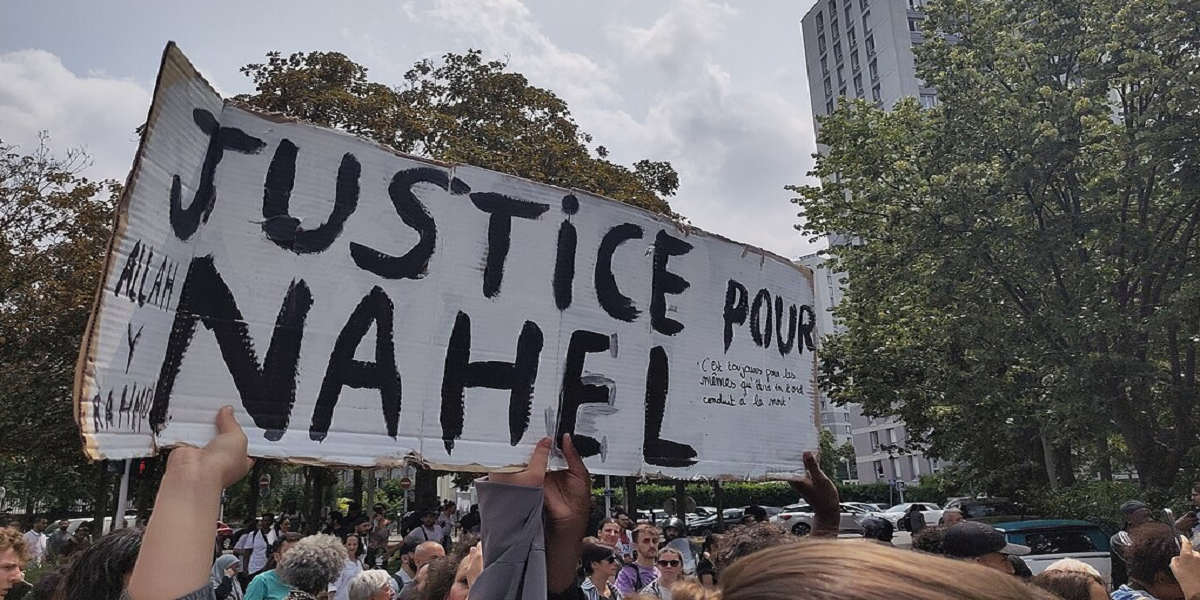

Because this time everyone saw, because this time everyone realised the police statement was fabricated, anger spread across the country. As one young man said to the press, ‘What happened in Nanterre this week was one time too many,’ before adding, ‘we are all Nahels today.’

Some call it a riot. Others call it a revolt. It doesn’t really matter. In the words of Victor Hugo: ‘What constitutes a riot? Nothing and everything. Electricity gradually released, a flame suddenly leaping forth, a drifting force, a passing breath.’ And so fireworks are aimed at the police; bins, bus-stops and cars burn. Police stations are targeted, as are schools and city halls. Stores are looted.

In response, the government sends the Research, Assistance, Intervention, Deterrence unit (RAID), an elite tactical arm of the French national police, the anti-gang brigade (BRI) also a unit of the national police, and the National Gendarmerie Intervention Group (GIGN), while the far right sets up a fund-raising campaign for Nahel’s killer. In just a few days, it collects over a million euros. A murder with benefits.

In the face of this revolt, the law responded not with justice, but with repression. To date, there have been more than 3,915 arrests made and 380 prison sentences handed down. France’s courtrooms waste no time when it comes to the young people from the banlieue. The streets chant slogans that have continued to be used since the first banlieue revolts in 1978: ‘We are not prey for the police!’

Our streets rage against the fact that a Mohammed is four times less likely to be hired than a Michel. Our streets shout against the fact that young men racialised as black or Arab are 20 times more likely to be stopped by the police. Our streets are screaming against a society that the United Nations described as having ‘deep issues of racism and discrimination in law enforcement.’

As we rightly focus on Nahel’s case and the fight for justice waged by his family, we must also consider the wider context. We live in a world in which Nahel loses his life for a traffic violation and the policeman becomes a millionaire for a bloody crime. A world where racialised minorities face specific forms of danger and violence.

And such a world order will only ever cause disorder, because peace is only possible through equality and justice. Without the latter, new riots and revolts will erupt. Whether it’s in France for Nahel, in the US for George Floyd, or anywhere else.

The state’s harsh and rapid penal response, called for by the government, only fulfils a desire for vengeance: no wound was ever healed behind bars. We denounce this approach. Instead, what the current moment requires is a serious discussion and a political overhaul with real, immediate solutions. The first step in this process would be the reconsideration of prison sentences given to those who revolted; we demand that all charges are dropped.

We also echo the calls put forth by the families of victims of police brutality, as well as activist groups and organisations. These demands include:

- Creating a fully independent body tasked with investigating police violence.

- Drastically restricting the use of firearms by police forces and banning all other lethal practices such as chokeholds and ventral tackles.

- Recognition of the racial and racist motives behind these forms of violence.

A few days after Nahel’s murder, another man fell victim to police bullets. He was shot in the chest with a defensive bullet launcher one night in Marseille while filming a police arrest. His name was Mohamed B. He was about to become a father for the second time. What other images were they trying to hide from us?

Now, everyone has seen. Now, everyone knows what happened.

Signed by:

- Angela Davis, author.

- Alice Walker, writer.

- Roger Waters, musician.

- Ken Loach, director.

- Judith Butler, philosopher.

- Annie Ernaux, writer.

- Eric Cantona, footballer.

- Mike Leigh, writer-director.

- Achille Mbembe, historian.

- Enzo Traverso, historian.

- Kali Akuno, activist.

- Amin Allal, political scientist

- Jean-Loup Amselle, anthropologist.

- Joseph Andras, writer.

- Kader Attia, artist.

- Marie-Aurore d’Awans, director.

- Adam Baczko, political scientist.

- Etienne Balibar, philosopher.

- Jeanne Balibar, actress.

- Ludivine Bantigny, historian.

- Fadi Bardawil, anthropologist.

- Jérôme Baschet, historian.

- Hajer Ben Boubaker, documentary radio producer.

- Omar Berrada, writer and translator.

- Olivier Besancenot, activist.

- Adèle Blasquez, anthropologist.

- Nadia Bouchenni, journalist.

- Rachida Brakni, director and actress.

- Sarah Carton de Grammont, anthropologist.

- Grégoire Chamayou, researcher and philosopher.

- Patrick Chamoiseau, writer.

- François Clusset, historian.

- Deborah Coles, human rights activist.

- Mickaël Correia, journalist and writer.

- Leyla Dakhli, historian.

- Jocelyne Dakhlia, historian.

- Gerty Dambury, afro-feminist writer and director.

- Dany et Raz, streamer.

- Veena Das, anthropologist.

- Slimane Dazi, actor.

- Marielle Debos, political scientist.

- Bintou Dembele, choreographer.

- Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, choreographer and dancer.

- Virginie Despentes, writer.

- Lukas Dhont, director.

- Vikash Dhorasoo, footballer.

- Penda Diouf, writer and actress.

- Alice Diop, filmaker.

- Assia El Kasmi, publisher.

- Mohamed El Khatib, director.

- Hassen Ferhani, filmmaker.

- Laurent Fourchard, historian.

- Peter Gabriel, musician.

- Pierre Gaussens, anthropologist.

- Laurent Gayer, political scientist.

- Faiza Guene, writer.

- Adèle Haenel, writer.

- Ghassan Hage, anthropologist.

- Rachid Hami, director.

- Kaoutar Harchi, sociologist and writer.

- Samuel Hayat, political scientist.

- Franck Henry, writer and producer.

- Sandra Iché, dancer.

- Imhotep and the band IAM, musicians.

- Donia Ismail, journalist.

- François Jarrige, historian.

- Laurent Jeanpierre, political scientist.

- Jul, cartoonist.

- Reda Kateb, actor.

- Perrine Kervran, documentary radio producer.

- Farah Khodja, actress.

- Lyna Khoudri, actress.

- KronoMusik, musician.

- Léopold Lambert, architect and editor.

- Paul Laverty, screenwriter.

- Léna Lazare, environmental activist.

- Frédéric Lordon, economist and philosopher.

- Steven Lukes, sociologist.

- Lylice, rapper.

- Maguy Marin, choreographer.

- Médine, rapper.

- Mehdi et Badrou, writers.

- MisterMV, streamer.

- Sepideh Moafi, actress.

- Marwan Mohammed, sociologist.

- Thurston Moore, musician.

- David Murgia, actor.

- Frédéric Paulin, writer.

- Jean-Gabriel Périot, filmaker.

- Thomas Piketty, economist.

- Anissa Rami, journalist.

- Candice Raymond, historian.

- Sandrine Revet, anthropologist.

- Ulrike Lune Riboni, university lecturer.

- Dennis Rodgers, anthropologist.

- Juliette Rousseau, writer and editor.

- Pascoe Sabido, advocacy officer.

- Felwine Sarr, writer and university lecturer.

- Mohamed Mbougar Sarr, writer.

- Marco Scotini, curator.

- David Scott, anthropologist.

- Seynabou Sonko, writer.

- Lina Soualem, filmmaker.

- Maboula Soumahoro, university lecturer.

- Ahdaf Soueif, writer.

- Lyes Taha, musician and producer.

- Rémy Toulouse, publisher.

- Victoire Tuaillon, journalist.

- Usul, vidéaste/streamer

- V (Eve Ensler), writer.

- Gisèle Vienne, choreographer.

- Louis Witter, journalist.

- Robert Wyatt, musician.

- Nathalie Zemon Davis, historian.