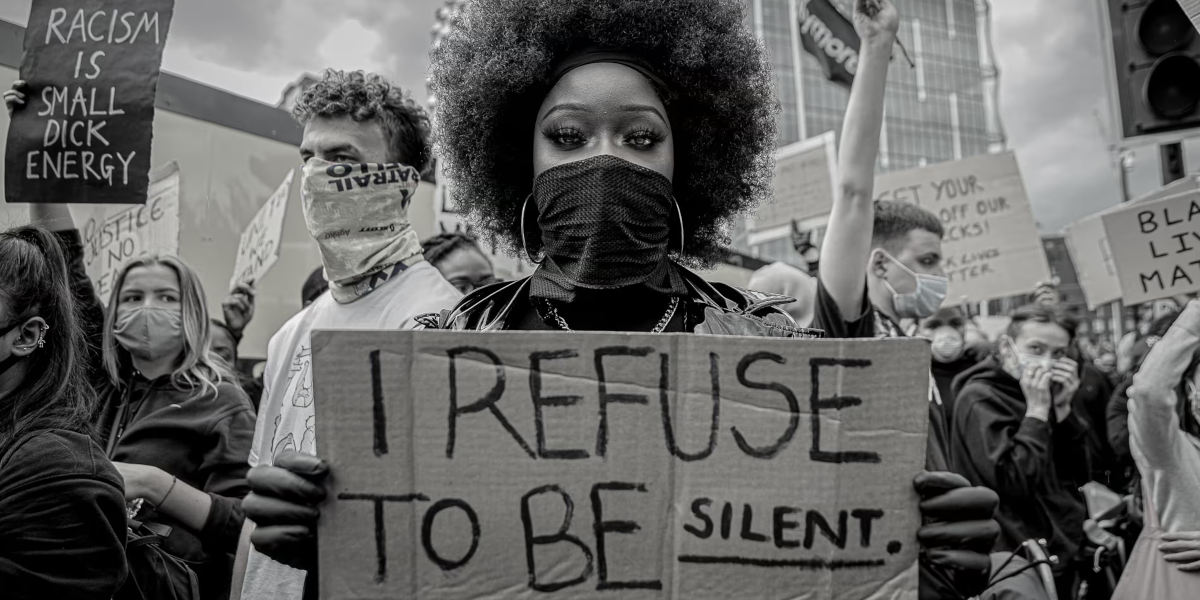

In a gallery in Brixton Village, there’s a large black and white photograph of a woman with an Afro and a sign. It reads ‘I refuse to be silent’. It’s not from the 1970s; the photo was taken in June 2020 after the brutal murder of George Floyd.

The gallery is run by Wayne Campbell, a photographer and visual activist. His space is called A Celebration of Demonstration – also the title of his iconic book about the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in London.

As the fifth anniversary of George Floyd‘s horrific murder approaches, I asked him what he felt had changed? He is succinct: ‘People’s appetite for protest’.

Before the murder of George Floyd, Wayne himself had never attended a protest. He worked within his community but not via protests. What changed? ‘I felt caught between two pandemics, Covid and racism’.

It’s been five years full of seismic world events. Ukraine and Russia went to war. Gaza is under siege. And the Covid-19 pandemic, which started so much upheaval, was quickly followed by the killing of George Floyd at the hands of Derek Chauvin. A death that is emblematic of systemic racism within America and beyond.

Fighting two pandemics

Some hoped it was a reckoning. For Wayne, it was the beginning of his journey into visual activism.

‘I asked myself what can I do? I’m not the get up and shout guy, but I had photography, that was my skill, and what I realised is, art is a powerful tool for political action, but also helps us understand and grow our political position and political awareness’.

No one can deny how powerfully visible the protests were, or how art was used within them: a feature of all protests that was amplified in those May demonstrations. Streets painted in six foot letters, the Black Panther aesthetic reborn, and the murder itself, imprinted on the eyes of billions aided by social media and global outrage.

But what has changed? Wayne is circumspect: ‘The defund the police campaign opened debate at least. And we saw brands come out and say they weren’t racist, but five years on it feels like not much has changed other than black visibility – in ads, for example, and to some degree in media and arts. But as a black visual activist, I and my peers still struggle to get real world backing, whether financial or practical’.

We all know that death at the hands of the police was not new to black communities across the black diaspora, particularly in Britain. The protests were particularly poignant for those communities. Communities like the one Wayne grew up in: Brixton, a borough historically scarred by police violence and racism, a place strengthened by black pride and black solidarity. That is what Wayne captured in that iconic photograph that dominates his gallery. That is what led him into the protests and on to create that first book.

‘Art is a powerful tool for political action, but also helps us understand and grow our political position and political awareness’

‘I wanted it to be our story. And I still want people to remember George, and the circumstances around why he died. I want us to acknowledge there’s still so much work to do, the protests were a profound first step’.

Regardless of Covid-19 restrictions and fear, people poured onto the streets of cities across the world, led by black people and joined, at last, by a mass of white faces. For decades since the civil rights movement, black people, predominantly men, have continued to be killed and harassed at the hands of police. Rarely since the concerts and actions in the 1970s and 1980s have white populations come onto the streets en masse and joined black communities in their grief and rage.

The 25 May 2020 changed that. The murder of George Floyd was filmed. Several angles, multiple witnesses. A captive audience, stuck in lockdowns, glued to screens. Hearts opened by their own losses. A reminder of mortality that Covid-19 interrupted white privilege with. Briefly the world lived up to one of Wayne’s favourite quotes: ‘It’s not enough to be non-racist, you have to be unapologetically anti-racist’.

A sentiment that seems to have left echoes of solidarity, but also caused the regressive voices of white supremacy to rise. That is why demonstration matters, Wayne asserts: ‘It is a spiritual, emotional and political form of resistance and it may not always change or shape policy, but it changes people, and eventually people change or reject what doesn’t serve them’.

A mission of solidarity

Wayne is clear when he says of his book: ‘It’s a historic document of what my community and the world were going through at a time of incredible social unrest’.

The first run of the book sold out, proving its value to the community at large. A second edition is going to print and will be available this year, the reprint featuring a forward by acclaimed writer and historian Paul Gilroy. The book’s ‘End word’ will address in depth what has and has not changed, and what we can all still do.

How are Wayne and his small team at A Celebration of Demonstration commemorating this fifth year and moving forward? Wayne himself plans to be in Minneapolis or New York. ‘I want to be talking to people about how Britain came together in support of George Floyd and the need for change. It’s a mission of solidarity’.

It sounds like a circle is being completed, taking the book to the place that, for a while, galvanised the world against racism.

Beyond the fifth anniversary, the ACOD team will continue to promote and create more historical documents on current protests, keeping alive the fire that was lit on 25 May 2020.

If you want to share your own journey into social, political or visual activism, and if you’d like to learn more and support their aims, you can find the gallery in Market Row, Brixton Village, or follow A Celebration of Demonstration across all social media platforms.