John Pilger is an award-winning journalist, author and documentary filmmaker, who began his career in 1958 in his homeland, Australia, before moving to London in the 1960s. He has been a foreign correspondent and a front-line war reporter, beginning with the Vietnam War in 1967.

For Pilger, ‘It is too easy for Western journalists to see humanity in terms of its usefulness to “our” interests and to follow government agendas that ordain good and bad tyrants, worthy and unworthy victims and present ‘our’ policies as always benign when the opposite is usually true. It’s the journalist’s job, first of all, to look in the mirror of his own society.’

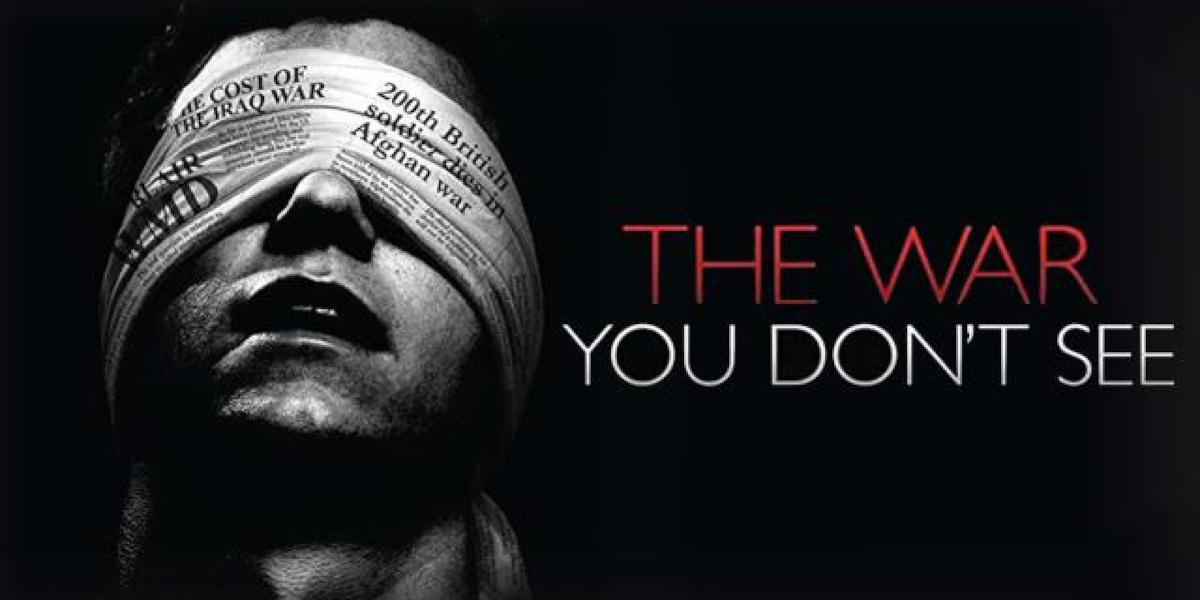

In a career that has produced more than 56 television documentaries, The War You Don’t See is Pilger’s second major film for cinema.

Pablo Navarrete

Your new film ‘The War You Don’t See’ focuses on the media’s role in war. I’d like to start by asking you why you felt you wanted to make this film.

John Pilger

Television is most people’s principal source of information. In Britain, much of television journalism is devoted to a mythology of ‘objectivity’, ‘impartiality’, ‘balance’. The BBC has long elevated this to a self-serving noble cause, allowing it to broadcast received establishment wisdom dressed as news.

This helps us understand why propaganda in free societies like Britain and the United States is far more effective than in dictatorships. While ‘professional’ journalists, especially broadcasters, present themselves falsely as a neutral species, truth doesn’t stand a chance.

This is most vividly demonstrated when imperial power – that is, America with Britain in tow – invades countries it wants to control, regardless of international law. This lawlessness is seldom a yardstick used in the coverage and selection of news.

I didn’t really understand this early in my career. Perhaps it was my arrival in Vietnam in the 1960s that helped me understand. The War You Don’t See is a product of that, and of routinely deconstructing almost every news item I see, hear and watch.

Pablo Navarrete

In an interview with Venezuelan academic Edgardo Lander, he argued that countries that do not have a democratic media cannot be called democratic.

Why is a functioning democratic media system so important for democracy in general?

John Pilger

I agree with Lander. Thomas Jefferson said, ‘Free information is the currency of democracy.’ It’s simple. No free flow of information; no democracy. Without an informed public, political or corporate authority – any authority – cannot be held to account, and if it’s not held to account, it’s very soon corrupted.

Pablo Navarrete

The British-based media watchdog website Media Lens argues that the increasingly centralised, corporate nature of the media means that it acts as a de facto propaganda system for corporate and other establishment interests. This is a damming verdict on mainstream journalism, but is it a fair one?

John Pilger

Yes, it’s entirely fair. Again, take the issue of war. The United States is a ‘warfare state’ with the most stable and powerful part of its economy devoted to the manufacture of armaments. It sells these armaments, and planes and munitions, to hundreds of countries. Go to any arms fair, and it’s clear these have to be ‘market tested’ in wars.

The cluster bombs that rain down on people in Iraq and Afghanistan were tested in Vietnam; the Napalm that has been refined to burn beneath the skin was tested in Korea. Each new war is a laboratory.

Much of the media and the arms companies are augmented; in the case of NBC, this is explicit. NBC is one of the world’s biggest news organisations and its parent company, General Electric, is one of the world’s biggest arms manufacturers. In the message of its news, the BBC is not very different. A study by the University of Wales, Cardiff, about the BBC’s role in the run-up to the Iraq invasion found that the corporation’s coverage was found to have been overwhelmingly supportive of the government – a government then engaged in serious lying, as we now know and as journalists ought to have known at the time.

There are of course a number of honourable exceptions, but think of an ‘establishment’ interest, then consider how it is propagated, directly or indirectly, in the so-called mainstream media; and by ‘indirectly’ I also mean a censorship by omission.

This surely must explain why so many in the media could barely contain their fury at Wikileaks; how dare these unclubbable types get in the way of the media’s right to be used and flattered and lied to. In The War You Don’t See, a former Foreign Office official describes in detail how easy it is to manipulate ‘lobby’ journalists.

Pablo Navarrete

Your film begins with shocking images from a 2007 US Apache helicopter attack on Iraqi civilians which first came out via the whistleblowers’ website Wikileaks. Last week, Wikileaks released more than 250,000 classified US embassy cables which have since dominated the global news agenda.

How important do you think the work of Wikileaks is and how big a threat does it pose to governments wishing to keep information about their foreign military operations secret from their citizens?

John Pilger

I hesitate to use the word ‘revolution’ but the entry of Wikileaks does represent a revolution. Digital technology has made it possible for governments to read our emails, but it also means we can read theirs.

Is this a ‘threat’ to established power? Yes, because, again, information is power. It gives an undemocratic elite its power and secrecy perpetuates this power. When we know the nature of official machinations and deceptions, we the public can act.

As the historian Mark Curtis says in my film, ‘the public is a threat that has to be countered.’ When the beans are spilled, the ‘countering’ is all the more difficult.

Pablo Navarrete

In your film you also recount how Edward Bernays invented the term public relations and pioneered the modern-day system of propaganda. And you show how the US government used Bernays’ techniques to recruit US citizens to join the First World War.

Are governments such as the US still using these techniques today, and if so can you give some concrete examples of how this works?

John Pilger

Edward Bernays said, ‘The intelligent manipulation of the masses is an invisible government which is the true ruling power in this country.’ The same techniques are still being used, such as the creation of what Bernays called ‘false realities’ and the rituals of patriotism devoted to justifying war-making.

What’s different these days is that the propaganda is not working. Look at the panic in the responses of governments to Wikileaks’ disclosures. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are opposed not only throughout the world but in the US and Britain. The world wide web has given people a way of finding out without turning on the TV or the Today programme.

I write a column for the New Statesman, which has a modest circulation. Once it goes out on the web, it can reach an audience of several million.

Pablo Navarrete

Finally, what would be the best way to make the mainstream media’s reporting of war less subservient to government interests and are you hopeful about the internet’s ability to provide alternative reporting of major events such as war?

John Pilger

The mainstream media will not change until its structure changes. A Murdoch newspaper or TV channel will always reflect the rapacious interests of Murdoch. However, journalists and broadcasters collectively have power, as does the interested public.

I would like to see established a ‘fifth estate’ in which journalists, and those in media colleges who tutor aspiring journalists, and the public, unite to begin to change practice from within. During the invasion of Iraq, there were small mutinies in the BBC, but they weren’t co-ordinated. The potential is there.

As for the internet providing an alternate reporting of war, that’s already happening. Most of the best reporting of Iraq was on the web – from the likes of Dahr Jamail and Nir Rosen, and ‘citizen journalists’ such as Jo Wilding. And it’s already happening where it probably matters most: at the seats of power, where, it seems, almost everything is leaking on the web; and long may it continue.