This October, 11 women from the UK and Germany travelled to the occupied West Bank of Palestine on a tour of friendship, solidarity and football. The motto of the ‘Freedom Through Football’ tour, was ‘we will share your story’ – our promise to share with the wider world the truth of life in Palestine and in particular to highlight the story of women who play (and excel) at football in a country where football for women is far from a cultural norm.

This recent tour is part of our growing story of friendship and solidarity between Republica Internationale (Leeds) and the Easton Cowgirls and Cowboys (Bristol) with Palestine. Our players have been travelling to the West Bank since 2007, with the women’s teams most recently visiting in 2014 and producing the ‘Balls, Barriers and Bulldozers’ film. Earlier in the summer, Diyar Academy had even travelled to the UK and met us on home turf.

Heading back to the West Bank this year joined by friends from Frau Dortebecker (Hamburg, Germany), we wanted to use a shared love of the beautiful game to stand in solidarity with those living under occupation in the West Bank.

If we’re honest, we had mixed success on the pitch. We won games against Hebron University, Beit Sahour and the Temporary International Presence in Hebron (TIPH). However, when it came to matching up against Sareyyet Ramallah and Diyar Academy (two teams that spend most of their time fighting each other to be crowned champions of the women’s league in the West Bank) we didn’t fare so well, with the games ending 8-2 and 13-6 respectively.

But, luckily for us, it’s not all about winning. Whether we were catching up with old friends from the Diyar tour, or being schooled by the quick, clever feet of Ramallah, each game gave us the incredible opportunity to meet some of the best footballers in Palestine and to better understand the challenges they face.

Many spoke of the difficulties playing football in a country where it’s still a ‘men’s game.’ “It’s hard to be a woman and play football in Palestine,” one Diyar player told us, “some people think that women shouldn’t play football, but we are challenging that and things are changing.”

It was clear that things were changing, too. Hebron University had played their first ever game of women’s football in 2014 as part of our first trip to the West Bank. Over the past 3 years, they’ve been playing matches against other teams in the West Bank and making connections with other women footballers across Palestine.

Others spoke of their frustration that women’s football is just not seen as on the same level as men’s football. This was something that was all too familiar to many of us, much to the surprise to many of the players we met.

However, the fight for equality on the pitch was often cast in the shadow of a wider fight for freedom in Palestine. For the women we met, the occupation created significant barriers to their ability to play where, and when, they want. Every checkpoint we passed was a reminder of the oppressive restrictions faced by Palestinians every day.

Before our first game against Diyar Academy, we travelled to Jubbet Al-Dhib, a village near Bethlehem. This incredible community, headed up by a women’s committee, had invited us to celebrate the delivery of shipment of materials to rebuild a healthcare facility in the village. However, as the delivery arrived, so did 8 soldiers from the Israeli Defence Force and two settlers from the nearby settlement.

We were questioned and asked for our passports, as the IDF soldiers absent-mindedly fiddled with the safety on their guns and the settlers took photographs of everyone. Our hosts, however, were determined to continue with their promise of breakfast. So we sat, between the village and the IDF, eating fresh olives, zaatar covered bread and grapes. After a lengthy stand-off, we were offered our passports back on the condition that we left the village immediately. We left, frustrated and confused.

We later discovered that the IDF had confiscated the building materials and the lorry that they had been transported on. The village would have to start fundraising for the health clinic’s renovations from scratch.

After our match with Diyar, we talked to some of the players about what had happened to us in Jubbet Al-Dhib. What had seemed pretty unique event to us was evidently an everyday occurrence for our Palestinian friends. This type of harassment was such a prevalent part of everyday life for Palestinians across the West Bank that it barely registered as an event.

Off the pitch, we also spent time in villages in the South Hebron hills, many of which had been threatened with demolition by the Israeli government. For two of us, one visit – to the Bedouin community of Um Al Khair – was particularly special. Last time they visited, the village had just been devastated by a demolition, the result of just one of many Israeli demolition orders placed on the community in the last few years.

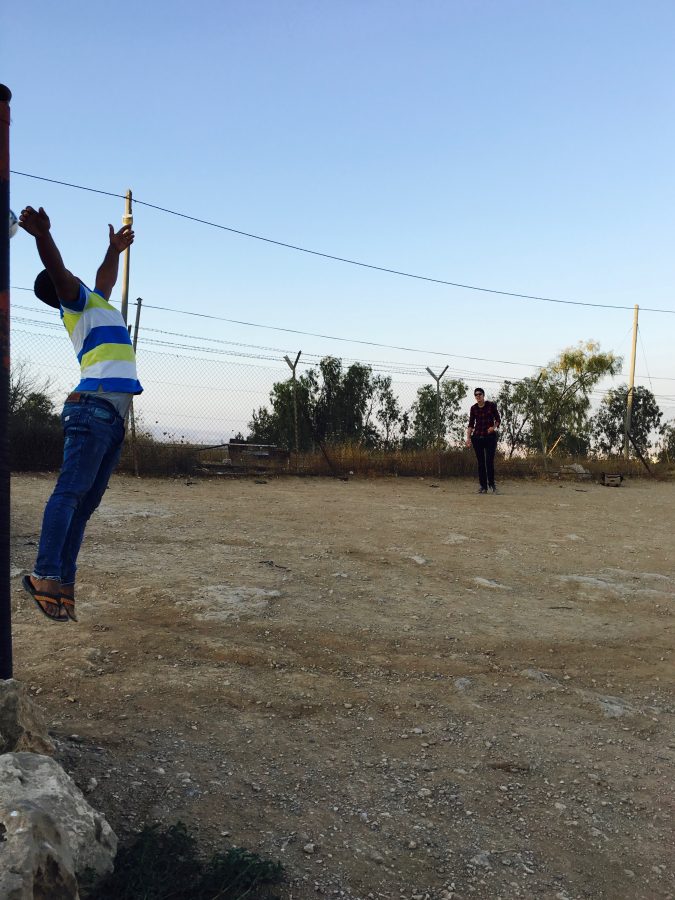

This time, we were able to return for tea in the rebuilt community centre, before heading to the dusty football field for a kickabout. We found out that the difficulties faced by the community were ongoing. An ever growing and imposing Israeli settlement – Carmel – is unfortunately all too literally, just a stone’s throw away. Residents in the village explained how the settlers throw stones at them whilst they are sleeping, just one example of the constant harassment they are subjected to.

The starkness of the divide between Um Al Khair and the settlement was all too clear. Watching the sun go down over the built, half-built, and demolished homes of Um Al Khair, the imposing wealth and privilege of the cream and red houses of the settlement was impossible to ignore.

Eventually, the football was booted over the 10-foot metal fence into the no-mans-land between the village and the settlement. As it bounced towards the well-manicured lawns of Carmel we knew this was one ball we weren’t going to get back.

As teams, we believe that football is about more than, well, football. Football has the power – and in some cases – a duty to challenge oppression, unite communities and create space for meaningful social change. At the very minimum, it starts a conversation.

Football gave us a unique insight into what life is like for Palestinians in the West Bank. What we saw, as much in the beautiful sports halls of Sareyyet Ramallah as the dusty playing field in Um Al Khair, was an incredible resilience to the daily aggressions of life under occupation.

Whilst football won’t remedy the injustices of the occupation, our experiences of playing football in the West Bank will hopefully start a conversation. We will share their story, and stand in solidarity with our friends in the West Bank, fighting for their rights to play, and stay, in their homeland.